Based on a lecture given at CAAPPR on 13 April 2022, as part of the celebration of World Landscape Architecture Month.

Culture and nature have been portrayed as contradictory or in conflict throughout many expressions of the Western tradition. From biblical literature to Christian theology to Moby Dick to La Charca, this conflict between nature and human society runs deep in our culture… Instead of domineering or “mastering” nature, today we have come to realize that nature has to be a partner in city living and that there is space for nature to thrive in the city… The relationship between nature and human culture, however, needs to be designed and managed, and here I provide three keys for that relationship to work.

1. Understand landscape architecture as mediator between human culture and (the rest of) nature, and as the fundamental practice for that relationship to work

Landscape architecture was a human practice tens of thousands of years before it was a profession. And there is much to learn from indigenous practices regarding landscape creation and modification attuned to natural cycles and processes. Before ecology existed, human wisdom developed on how to relate effectively to the rest of nature and how to be prosperous together. Going back to that wisdom, with our current ecological understanding, makes a lot of sense and might help us survive current crises. Landscape architects are especially prepared to take a look at indigenous traditional landscape practices and apply them to human habitations around the world today. That is the work, for example, of landscape architect Julia Watson.

Beyond the wisdom from indigenous practices, landscape architects today are well prepared to lead the charge in bringing nature back to cities in an ecologically meaningful way. With sensitivities both to the workings of nature and human culture, landscape architects bring a unique perspective to the planning and design of better city environments where both humans and wildlife can thrive together.

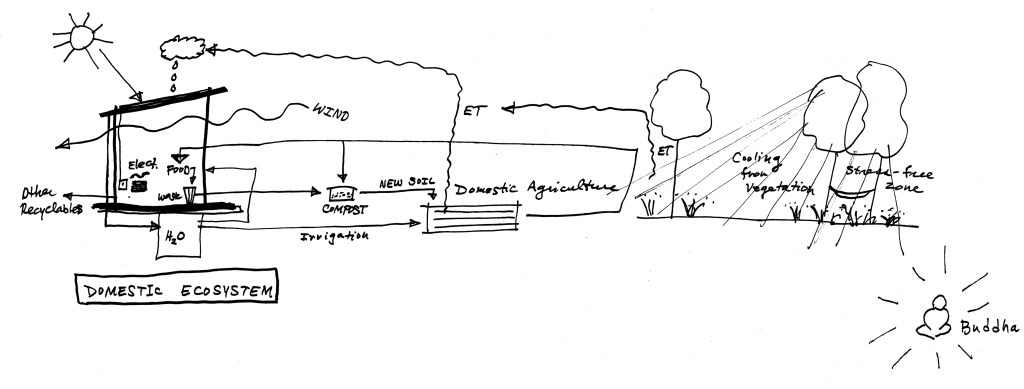

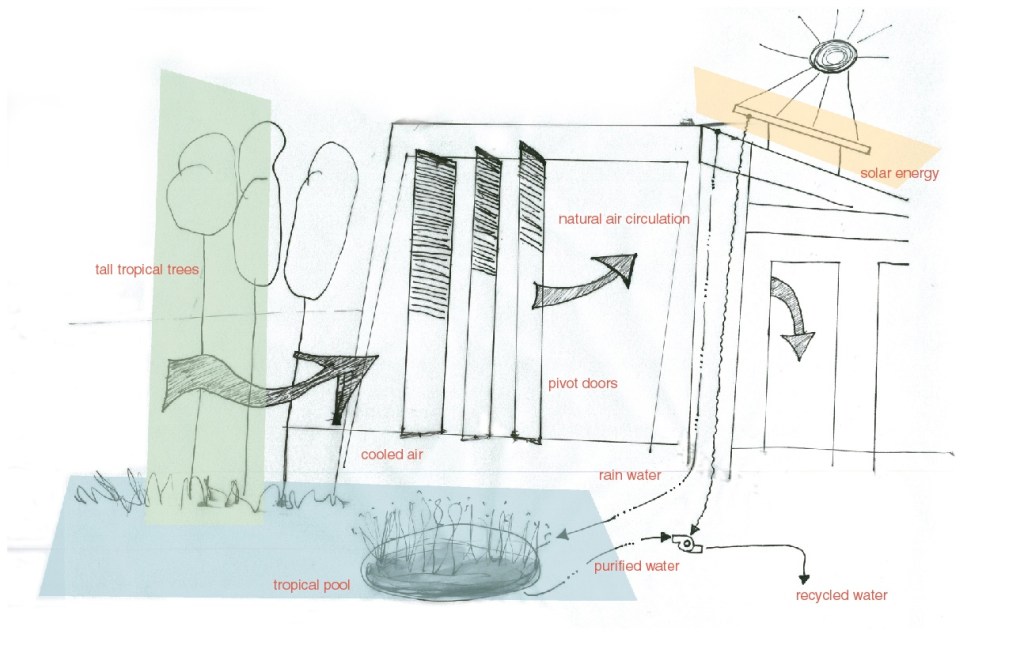

Cities must be thought of as ecosystems and nature in them as parts of this ecosystem, put there by the landscape architect to do a particular job. In this respect, we hold a post-conservationist and eco-functionalist view of nature. We need “deep-nature” in the city – not just plants that serve to “decorate” and make it “look nice.” Nature in the city must do work, must be part of a total, functioning system. At the same time, nature in the city must have its space to thrive and support wildlife. Long gone are the days when nature was restricted to “reserves” and to “conservation areas.” Cities must also function as conservation areas, as spaces where wildlife can survive and prosper. If we keep dividing and sub-dividing the realms of human culture and nature we will loose both. Human culture and nature must thrive together and the model for this comes from a landscape architectural design of cities based on mutualism. In mutualism both organisms benefit from the relationship, often a physical, close-contact relationship of co-functionality, i.e., providing a function the other lacks.

But nature in the city is not just “infrastructure.” Nature in the post-conservationist, eco-functionalist city is a cherished creator of space, generator of city, spatial expression, and as spatial expression, nature in the city is also art. Nature in the city, while performing many functions, while having its own space and its own rules, must also aspire to the sublime. Nature in the city is also a living medium to human artistic expression. And here, perhaps, lies the fundamental connection between human culture and nature: it is a relationship that supports more than mere physical survival, it supports mental and spiritual health and wellbeing.

And this is why landscape architecture is such a tough profession. The vision of the sustainable, resilient, ecological city is a vision where nature and human culture are integrated and hard to tell apart. While partly a “machine” that must perform certain functions for survival, the city is also a physical expression of human culture that aspires to embody the highest values of a society and to celebrate the beautiful diversity of life on this planet. Landscape is, thus, this cyborg that marries natural elements and human artifice for both human and wildlife to thrive.

The city as a cyborg landscape, where culture and nature are in an intimate, mutualistic relationship, does not exist by chance, does not arise spontaneously. Landscape architects are called to mediate this condition, to plan for it, to design it…. and, eventually, to help maintain it. But this cyborg landscape must be rooted in its history, its identity, its cultural milieu for a society to embrace it and make it its own. “Ownership” along with identity bring care, and love. And a city’s cyborg landscape must be loved to endure…

2. Acknowledge landscape as a cultural product that reinforces identity and a sense of belonging

Landscape is always a cultural product. It is always an interpretation of the human mind about the relationship between natural elements and human elements in the environment. Landscape can be created just by human perception of its environment and it is born of the ideas of a human mind about those perceptions. I always tell my students that if all humans were to disappear from Earth instantaneously, all landscape would also disappear. Of course, trees would remain, rivers would remain, coastlines and cities would remain. But all of those things are not landscape without a human mind to create it or to interpret it. And humans have been creating and disseminating landscape for over one million years already.

Globalization of human culture started when the first humans left Mother Africa, perhaps 60,000 years ago. Since then, humans have taken concepts of landscape across the globe and their favorite species along with them. This creation and co-creation of landscape between cultures is fundamental to the human condition. The Caribbean today is obviously not the same place on Earth that it was 600 years ago. The movement of humans, accelerated since 1492, has also meant an evolution of landscape concepts.

My idea of the Caribbean landscape comes from growing up in my grandmother’s garden. A garden that served the kitchen, but that also contained a lot of tropical color: orange-flower heliconias, brilliant-red hibiscus, and amazingly purple bougainvilleas. My grandma’s garden taught me which herbs to use while cooking a Puerto Rican meal, but it also taught me that the Caribbean landscape is about intense colors, including the infinite variety of greens…. In a very concrete and real sense, landscape is identity.

Those deeply created concepts of landscape do not go away easily and that is why new landscape has to be familiar to its users. The re-designed sectors of a city have to engage its inhabitants, lest the new landscape simply marginalizes them. Who is to say that a flamboyant tree (royal poinciana), native to Madagascar, should not be planted in a Puerto Rican city because it is non-native? Or a coconut palm on a Puerto Rican beach?

We often hear arguments, mainly from outside landscape architecture, that we should only plant native species. But, how can we give continuity to our concepts of Puerto Rican landscape without naturalized species, like the flamboyant tree or the coconut palm? How can we build or re-build Puerto Rican landscape without the species that define it today?

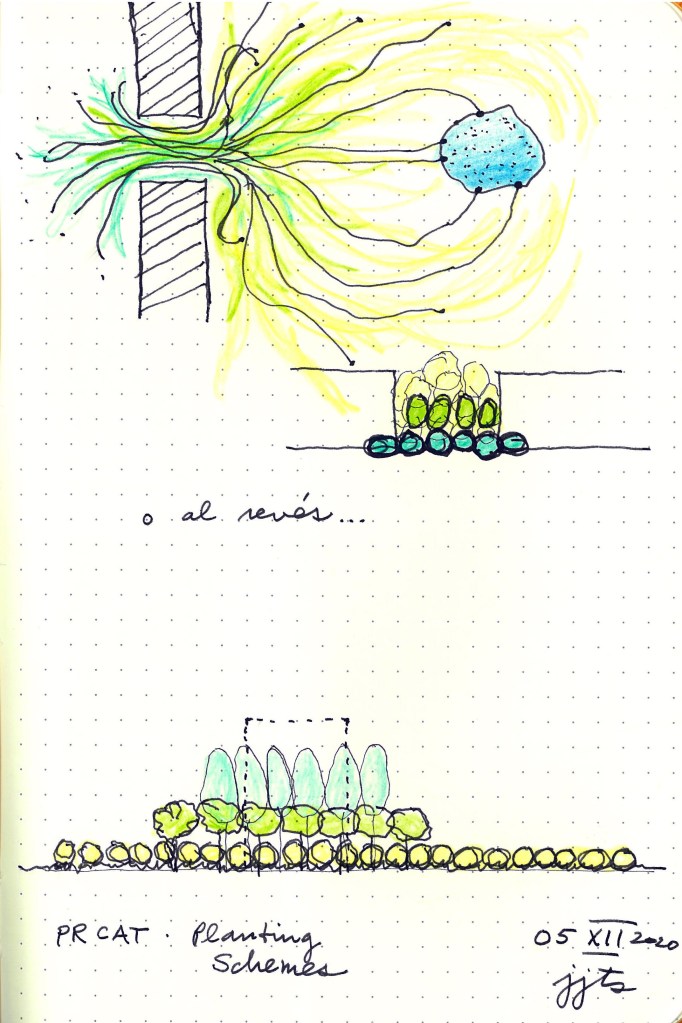

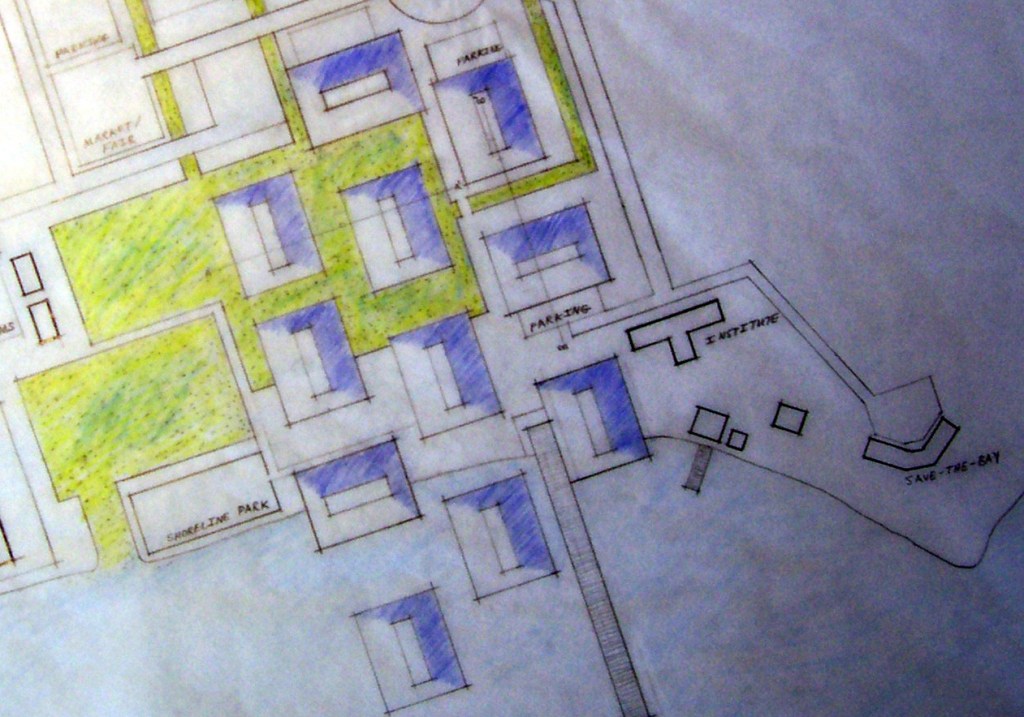

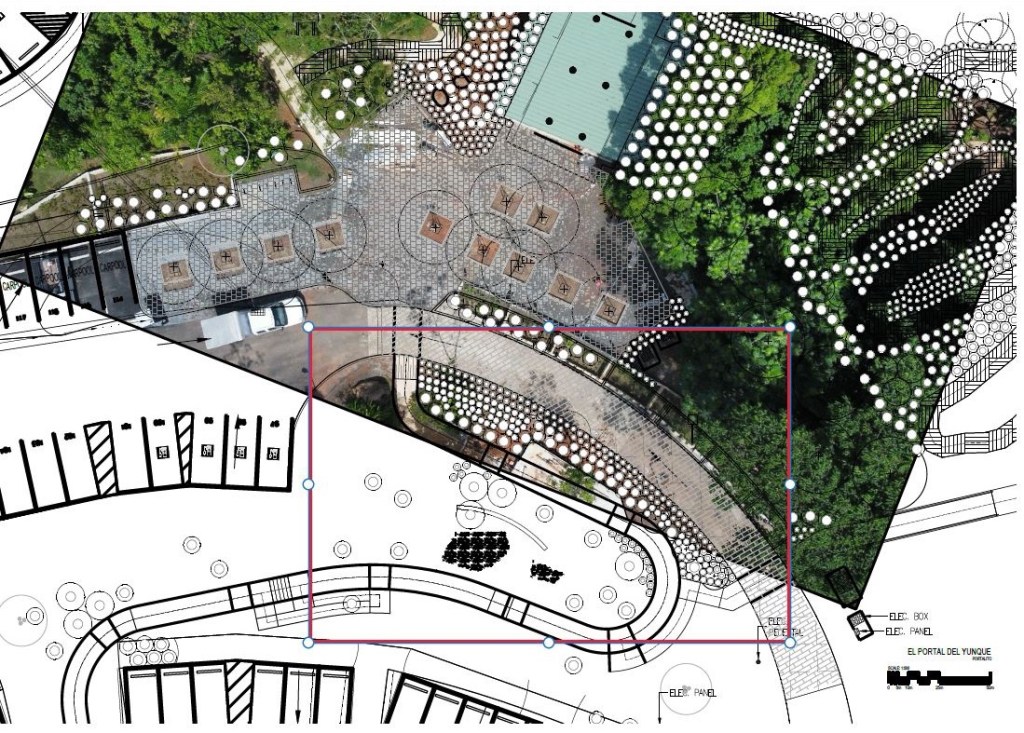

At the office we pondered precisely that question while developing concepts for the complete re-design of the landscape and site of El Portal, the visitor’s and community center at El Yunque National Forest, administered by the US Forest Service. The Forest Service design brief said to only use native species, not only to Puerto Rico, but native to the region of the Luquillo Mountains, where the forest is located. While this makes sense from an ecological point of view, from a landscape architectural point of view it hardly makes sense.

We eventually reached a middle ground with the Forest Service and successfully argued that, while Luquillo native species were appropriate close to the forest itself, as one approached the building of El Portal it would make sense to use naturalized species also, particularly those that have been in the Puerto Rican concept of tropical landscape for a long time…

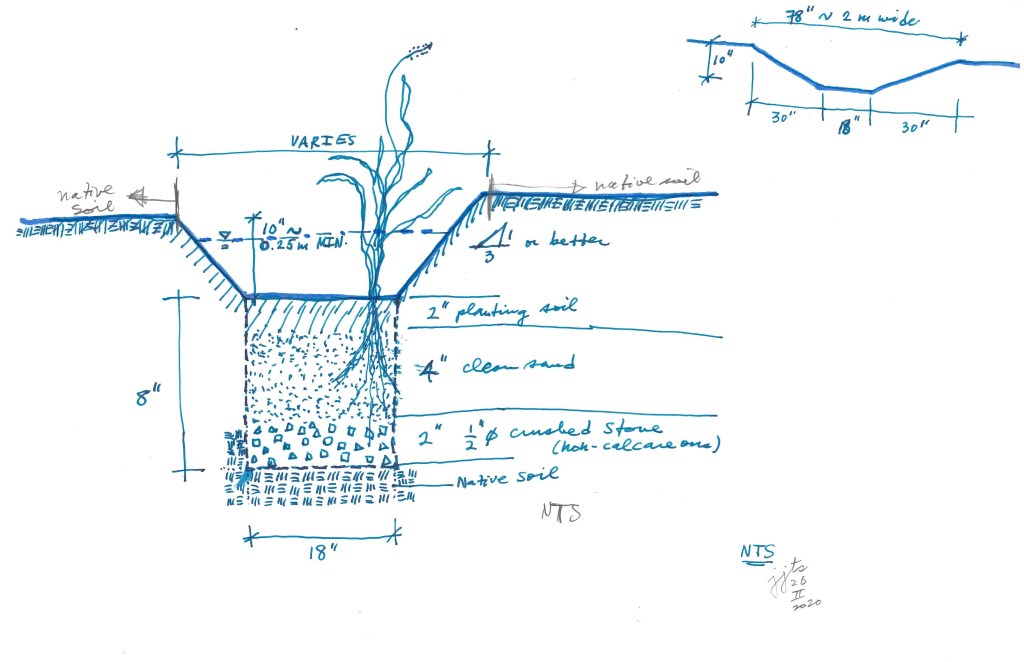

When new landscape is grounded in familiar cultural concepts, while innovating with new experiences of space, materiality and ecology, it is both culturally appropriated and cherished. And that is the experiment at El Portal. The blending of familiar cultural concepts of landscape with rarely seen native species (like ortegón) and new spatial ideas (like enormous bioretention cells) is intended to create something unique that feels authentically local.

3. Let nature be a functioning, self-sustaining, part of landscape in the city

Nature performs work in the city; it is not merely a visual amenity. It stabilizes slopes, cleans water, manages peak flows, refreshes air, controls heat, provides habitat, reinforces or conceals a view, provides a nuanced and layered experience of space, and performs so many other functions…

For a city, or a human environment in general, to work, it needs a basic level of ecological functioning. Instead of prescribing native plant species indiscriminately, landscape architects need to think about the Life-Water-Soil-Air interactions and the processes they create through the design of human environments.

Of course, the landscape architect must pursue biodiversity, a wholesome or complete hydrological cycle, healthy soil, clean air, and an adequate microclimate. All of these are elements of a healthy urban ecosystem. And nature is a key ingredient to achieve a healthy urban environment. But we as landscape architects also understand that the landscape assemblage that we put together is a cyborg, a combination of natural and built components that must work together for nature to thrive and for people to thrive in cities. We must also recognize that the design of urban landscapes is the design of initial conditions, not of final ones. Landscape architects must account for the dynamism of the landscape cyborgs they create and their ability (and necessity) to change and adapt to many different changing variables and conditions over time. We must allow for the ecological succession and the social evolution of designed human environments to work together and support each other.

At Marvel (www.marveldesigns.com), we designed small parks for the Caño Martín Peña communities that were imagined as social and natural successional systems. The vision for these small parks is to create community empowerment through the use of space and the establishment of new ecologies, closer to the original ecological functioning of these sites.

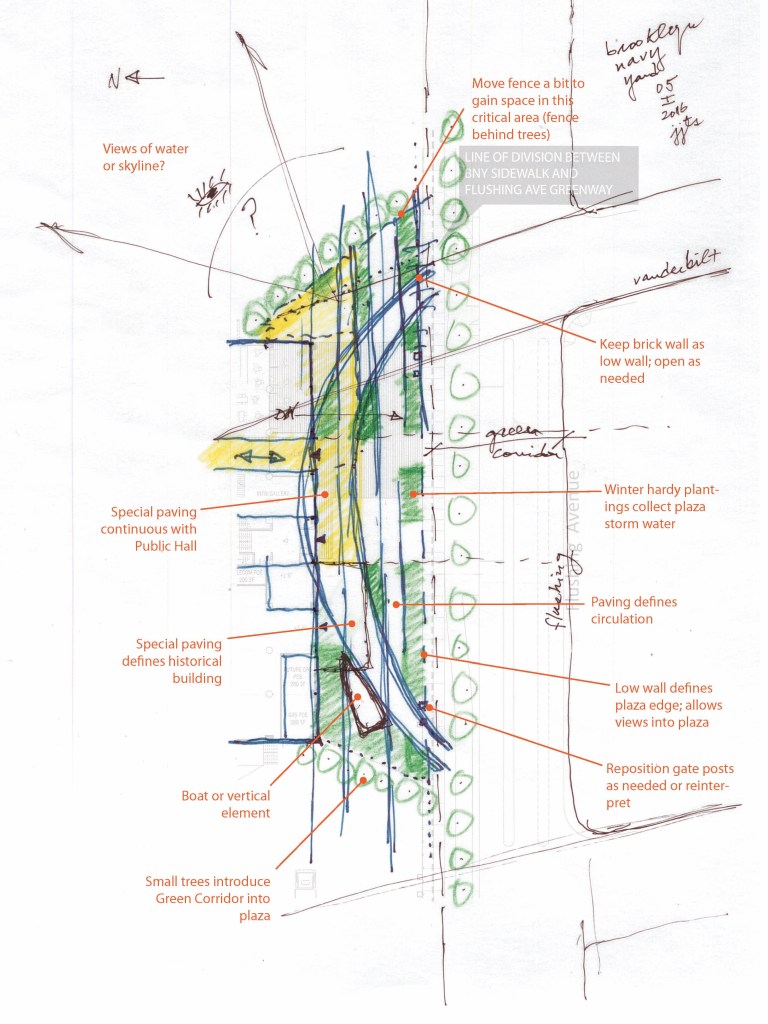

Whatever we do, we need to provide sufficient space and conditions for nature to be self-sustaining and function autonomously in the city. Providing that space and those appropriate conditions in the city is often difficult and it is a balancing act between natural and constructed elements. An example is when we provided structural soils in the Building 77 Plaza at Brooklyn Navy Yard for vegetation to survive the sometimes extreme conditions of the city… Structural soils allow trees to survive in a fully programmed, fully hardscaped city plaza. The structural soils provide space for roots and adequate moisture and gas exchange. Soils are living entities even in the city, and their health and good functioning are critical for nature to work in the city and to thrive autonomously.

The relationship between human culture and nature must be mediated, must be designed, in order for it to work. And landscape architects are here to make that happen. We must inject cultural significance to the experience of nature in the city, while giving nature enough resources to be self-sustaining in the urban environment. At the end, it is all about BALANCE and taking seriously the mediator role of the landscape architecture profession: upholding and articulating the immense richness of human culture everywhere in our world and making room for the rest of nature to share our space in a truly mutualistic relationship. Our survival as a species might depend on it.