Presentation (in Spanish) on ecological urban design:

LANDSCAPE + IDEAS

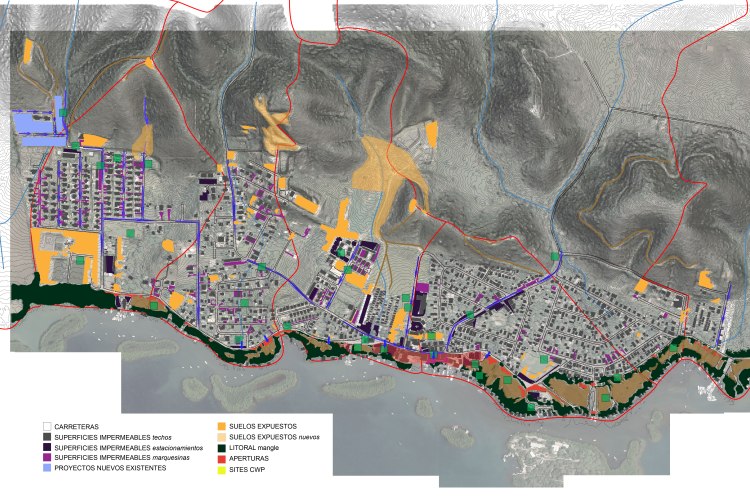

La Parguera Analysis

Designing Nature as Infrastructure – Symposium – Technische Universitat Munchen, Munich, Germany

Here’s the Symposium poster and program. We will present on a Green Infrastructure Plan for La Parguera, Puerto Rico.

La Mancha is an impossible landscape to understand easily; it is quite difficult to know it deeply… But an amazing landscape it is…. One full of history and meaning to us Spanish-speakers…. The Tajo River is the lifeblood of the Upper La Mancha… A river of contradictions, silent witness of life and death…. Life-giver and backbone to the rest of the landscape…. A symbol of life in La Mancha…. To all my Manchegan friends: a remembrance of unique and unforgettable moments shared…. La Mancha, remembered; now part of my mind continuum….

La Mancha is an impossible landscape to understand easily; it is quite difficult to know it deeply… But an amazing landscape it is…. One full of history and meaning to us Spanish-speakers…. The Tajo River is the lifeblood of the Upper La Mancha… A river of contradictions, silent witness of life and death…. Life-giver and backbone to the rest of the landscape…. A symbol of life in La Mancha…. To all my Manchegan friends: a remembrance of unique and unforgettable moments shared…. La Mancha, remembered; now part of my mind continuum….

“Reinterpretar el paisaje” [La conservación de los paisajes de Don Quijote / Conservation of the landscapes of Don Quixote], El Nuevo Día, San Juan, Puerto Rico, 17 de noviembre de 2007 –> JJ Terrasa, El Nuevo Día, 17 NOV 2007

(Plan for the Río Tajo Valley at Toledo, Castilla-La Mancha Studio, GSD, 2006)

La luz del Tajo en Talavera

La enrarecida luz del crepúsculo bañaba el usado puente de antaño,

Mientras los pétalos blancos, prolongaciones de las blancas manos que los lanzaron,

Acariciaban la piel del viejo padre en su ir al Atlántico…

Del Padre Río Tajo que esa tarde sonreía en destellos variegados

Reflejando el paisaje primaveral, multicolor, que viejas sociedades cultivaron

Y que hoy aprecian sus nuevos hijos, deseosos de salvarlo…

En mis 39 años de vida natural y 10 de vida profesional no había visto yo un gesto tan significativo y concreto sobre la vida de un río. El ofrendar flores al río en aquella mágica tarde primaveral en Talavera de la Reina encierra en sí un profundo significado que mueve corazones y aúna voluntades. El ofrecer vida a la fuente de la vida cierra un ciclo perfecto en el orden natural que simboliza todo lo que es renovación, renacer y resurrección. Así se reunía un grupo de lugareños y recién conocidos extraños en una causa común que los unía en perfecta comunión de mentes y corazones.

El acto de celebración del Río Tajo, aquella tarde sabatina talaverana, concluía de forma muy emotiva lo que fueron unos días de pensar y sentir el río que una vez fue la base absoluta de la vida por estas tierras. Las Jornadas del Tajo lograron reunir en Talavera de la Reina grandes mentes y grandes corazones de toda España y aún de allende los mares. Está claro que para poder amar y convivir hay primero que conocer y apreciar. Y esto es lo que esencialmente fueron estas Jornadas: conocernos y apreciarnos; conocer el río y apreciarlo en sus valencias y extensiones para poder amarlo más y mover la voluntad por él.

Así como el río es una corriente que enlaza su cabecera con su desembocadura, así también es un hilo conductor de recuerdos, de personas, de generaciones y de culturas. La historia de un río es la historia también de sus gentes y de los paisajes que componen su cuenca hidrográfica. Quizá un río, mejor que un tomo de historia, cuenta los afanes y amores de sus gentes. Como ande un río, así andará también una sociedad y lo que ella profese como valioso. Por lo que aunar esfuerzos por la recuperación de un río es también aunar esfuerzos por una mejor sociedad, por una sociedad más justa, más balanceada, y más humana.

Las Jornadas del Tajo en Talavera fueron también una rara unión de ciencia y conciencia. De poner el saber al servicio del sentido de justicia que mueve a las múltiples entidades empeñadas en recuperar uno de los mayores valores del territorio de Castilla-La Mancha. El Río Tajo podría ser un corredor verde, elemento vertebrador del paisaje y vía recreativa para ciclistas, senderistas y piragüistas. También podría ser infraestructura verde: elemento funcional que depure las aguas e instrumento de hacer trabajo para la sociedad. Todo esto, por supuesto, sin perder su función de ecosistema acuático y ribereño, que si no la tuviera, no podría ser todo lo demás.

Y he aquí la clave para visualizar un futuro mejor para el río: su mejoramiento integral va más allá de simplemente aumentar los caudales. Su mejoramiento tiene que incluir también el compromiso de restaurar su riberas para que funcionen mejor ecológicamente hablando; aumentar los accesos al río para que la gente aprenda a usarlo como recurso recreativo y aprenda a valorarlo como elemento definitorio del paisaje castellano-manchego; y diseñar mejores espacios públicos asociados al río para que el río adquiera nuevamente un rol cotidiano en la vida de sus hijos e hijas. De esta forma, la recuperación del Río Tajo requiere la integración de muchos puntos de vista y muchas disciplinas: la hidrología, la ecología, el arte, la historia, el derecho, la arquitectura paisajista, los usuarios recreativos, los agricultores, los ciudadanos comunes, los oficiales de gobierno, en fin, de todos los que en una democracia hacen la diferencia.

Que el entusiasmo que compartimos durante esos tres días se transforme en acción concreta y en compromiso por salvar el paisaje del corazón de España.

(JJTS, Jornadas del Río Tajo, 20 al 22 de abril de 2007, Talavera de la Reina, España)

It was instantaneous like a hot fire raging through the forest it took everything on its path destroyed demolished eliminated with a sweetness and tenderness unseen before it was wild and free it was animal it was instinctual without thinking like magnets attracting accelerating to each other until contact made the explosion obvious and plainly observable by all in awe the fire started and burned with delight leveling all obstacles and rendering them insignificant friendships and old relationships all made trivial in a moment of fire how ridiculous but how right it felt at the moment our eyes crossed in that one fortuitous space on that one second of truth of light forever of coming home of never going back all things thrown over and all things rebuilt at once yesterday and tomorrow united in nothingness only now and now forever its only virtue lies in pure presence and in pure truthfulness even though a rain of tears washed away any enjoyment or fleck of pleasure now nested on the sugary ashes are memory and nostalgia and stillness and the peace of realizing evolving suchness…

The Buddhist tradition is essentially about the discipline of the mind to attain Enlightenment or transcendental wisdom, but its techniques and outlook can (and should, for the Buddhist) be applied to any task at hand, including design. The application of Buddhist thought as a non-religious, philosophical outlook to engage daily life, from psychology to literature, is generally referred to as the “Mindfulness Movement.” To be mindful is to be present here and now; to go deep into the present moment, with all its complexity and to the full extent of experience; to exercise the mind in order to be able to focus its attention. The idea is that we can live richer and happier lives if we learn to stop and appreciate fully our life experience in the here and now. Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh, for example, has written extensively about mindfulness and its application to daily life (see http://www.plumvillage.org/thich-nhat-hanh.html and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thich_Nhat_Hanh).

It would seem, however, that mindfulness and design are just incompatible. The phrase “mindful designer” seems to be, at first glance, just another cute oxymoron. How is it possible to be mindful as a designer if a designer (landscape architect, urban designer, architect, engineer, etc.) is concerned mainly about the future, about a potential reality that is not here and now? Conversely, why would somebody bother with the hard labor of design if the present is so wonderful and rich?

I think this apparent contradiction dissolves when we look at the new ways of thinking about the design process and the role of the designer, coming mainly from landscape architecture, on one hand; and, when we look deeper at some of the basic Buddhist ideas behind mindfulness, on the other.

One of the fundamental insights of the historical Buddha or Shakyamuni Buddha (563-483 BCE), is the idea that all of reality, including ourselves, is in constant flux; the idea that everything is empty of true independent being or that everything is impermanent. The practice of meditation and the techniques of mindfulness help us to focus our mind so that it is not carried away in this constant internal and external flux of events and ideas. While the mindful person recognizes the importance of dwelling in the present moment, they also learn to recognize the complexity of the world we experience as reality and the interdependence of all the “systems” that form that reality. (Despite that for the Buddhist the ultimate nature of reality can only be known to the fully enlightened mind, our mental constructs of reality can help us “bend the flux” of events to obtain different, advantageous outcomes.)

It is precisely this “systems” way of understanding reality (e.g., “the landscape”) that is at the base of over 100 years of theory and practice in landscape architecture. Other design disciplines, particularly urban design, have also turned to a systems (or ecological) approach, instead of being merely preoccupied with form and visual experience. The systems approach in design begins by recognizing that a landscape, a city, or even a building, is a complex made out of interrelated systems that are in constant flux. When the designer recognizes this simple (Buddhist and ecological) truth, the role of design completely changes from its traditional conceptualization.

The traditional view is that the designer defines a set of conditions for the construction of a building, a city or a landscape, and that those conditions will constitute a final and permanent reality. The view that has been used in landscape architecture, and in other disciplines more recently, is that the designer does not define a final reality but instead sets in motion a complex of systems that will have its own (interdependent) life and will be affected by many factors beyond the control of the designer, and even beyond the control of the “operator” of the building, city or landscape. This “setting in motion” of a complex (or bundle) of systems is equivalent to the “bending of the flux” that I mentioned above.

So, how can one be a “mindful designer” or how can one practice mindfulness in design? I propose the following characteristics of the mindful designer and elements of mindful design:

The practice of mindfulness, and the Buddhist principles it comes from, opens a lot of possibilities to the designer. It gives the designer the opportunity to approach a site and a design project with a clear, uncluttered, and pliable mind; it allows the designer to be more sensitive to the here and now, and eventually allows them to be more effective in obtaining an advantageous result. I am willing to bet that, at the end, and with sufficient practice, the mindful designer will produce ever more wonderful places in which to live, work, play, and experience the beauty of every moment, here and now.

INTRODUCTION

One of the most important skills of the landscape architect is to realize connections in the landscape. “Realize” is meant both in the sense of understanding and in the sense of achieving or building. Realizing connections might be, in fact, the essence of what a landscape architect does, given our current understanding of “landscape” as a web of natural and built systems.

Many landscape architects, like Larry Halprin, have included deep observation of the landscape as part of their formal practice of landscape architecture. Halprin, for example, recommended immersion into the landscape to be intervened before any design idea was developed. This immersion can take various forms: from freehand drawing of what exists (which is fairly common within the profession) to camping at the site for a few days (which I don’t think is common). In all cases, however, the practice is essentially intended to increase one’s awareness of connections in the landscape and to be fully present at the site at a particular moment in time.

I believe that immersion into the landscape to be intervened is very important for the landscape architect and that various forms of meditation can help to sharpen the mind in order to be present at the site or landscape more fully, to realize connections, and to feel/see what is not evident at the site.

Buddhist tradition is rich in meditation practices directed at mindfulness: being fully present here and now. In Buddhism, the idea of the connectedness of all reality through the law of cause and effect is paramount. Thus, Buddhist meditation offers a great opportunity to the landscape architect to sharpen the mind and develop observation skills needed to understand the complex reality of landscapes.

I offer here a simple meditation-in-action: the peeling of a fruit (a papaya in this case). The Zen tradition of Buddhism, in particular, perhaps has developed more than any other the “meditation-in-action.” It is in that spirit that it should be practiced.

MEDITATION

Four alumni of Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design (GSD) are founding faculty members of the first landscape architecture program in the Caribbean. Olga Angueira, M.L.A. ‘04, José Lorenzo, M.A.U.D. ‘05, Edmundo (Mundy) Colón, M.L.A. ‘06, and José Juan Terrasa-Soler, M.L.A. ’07, teach at the new School of Landscape Architecture of the Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico, in San Juan. The School offers a 3-year Master of Landscape Architecture (M.L.A.) program, which opened in August 2006 and graduated its third class last June. The proposal for the School was originally developed by landscape architect Marisabel Rodríguez and architects Jaime Suárez and Jorge Rigau, who recruited the first faculty, including the four Harvard alumni.

One of the very few landscape architecture programs located in the world’s tropics, the Polytechnic’s program has already graduated 22 new landscape architects. When the School opened in 2006, there were only about 35 landscape architects in Puerto Rico. Thus, this program alone has caused a 63% increase in the number of these professionals on the island. The M.L.A. program is also raising regional interest and a student from Guatemala recently graduated.

The curriculum is structured around a sequence of core design studios that take students from the garden scale all the way up to the urban and regional scales. The disciplinary focus on systems – natural, social, and built – is stressed both in theoretical and in design courses. The students’ academic experience is capped off with the development of a design thesis, which must be defended before the faculty.

Faculty research focuses on the history of landscape architecture in the Caribbean, with emphasis on Puerto Rican landscape architecture. Another important focal area of research is the adaptation to the tropics of green infrastructure concepts developed for temperate landscapes. Most faculty members, including the Harvard alumni, combine teaching and research with professional practice in the public and private sectors.

The Polytechnic M.L.A. program has been accredited by the Puerto Rico Council on Higher Education and recently went through a successful accreditation visit by the Landscape Architectural Accreditation Board (LAAB), which accredits landscape architecture programs throughout the United States. The Polytechnic M.L.A. program expects to receive LAAB accreditation this Fall.

Niall Kirkwood, Professor of Landscape Architecture and Technology at the GSD, and GSD alumna Kathryn Gleason, M.L.A. ’83, were members of the accreditation board that first reviewed the program for the Puerto Rico Council on Higher Education.

“Having the opportunity to collaborate with other recent graduates of the GSD in a foundational project like this is extraordinarily exciting and fulfilling,” says José Juan Terrasa-Soler, M.L.A. ‘07. “The rigorous training we received at Harvard prepared us to break new ground in Puerto Rico and the Caribbean,” he concluded.

PROGRAM WEBSITE: www.pupr.edu/gs/landscape-architecture.asp

Ha surgido nuevamente discusión pública en torno al Plan de Usos de Terrenos de Puerto Rico (PUT), que lleva años gestándose por parte de la Junta de Planificación de Puerto Rico (JP). El PUT intentaría darle a Puerto Rico entero una base para la planificación del país, que hasta el momento ha tenido planes que atienden principalmente las zonas urbanas de sus 78 municipios y alguna que otra área especial.

La renovada atención se debe en parte a la publicación reciente del volumen número 18 de la Revista Entorno, publicada por el Colegio de Arquitectos y Arquitectos Paisajistas de Puerto Rico (Colegio) y dedicada al PUT (http://www.caappr.org/index.php?node=1118). Incluidas en ese número están una serie de recomendaciones que hace el Colegio como institución al proceso de desarrollo del PUT. El lanzamiento de ese número de la revista se hizo simultáneamente con un conversatorio público sobre el tema del PUT, celebrado el 7 de septiembre de 2011 y en el que participaron el gobierno y diversos sectores de la sociedad.

A pesar de las mejores intenciones de todas las partes, falta en la visión de la JP, y hasta en las propias recomendaciones que hace el Colegio, una perspectiva de paisaje que integre todos los temas materia de planificación y permita producir un verdadero plan integral para el desarrollo de Puerto Rico. Es importante anotar que por paisaje se entiende el complejo interoperante de todos los sistemas naturales, edificados (culturales) y sociales de un territorio particular.

La perspectiva de paisaje produciría una visión físico-espacial de lo que se quiere conservar y mejorar como el armazón imprescindible de apoyo a la vida para el desarrollo de Puerto Rico. Para imaginarnos lo que sería ese “armazón paisajístico” podríamos preguntarnos: ¿Qué elementos de nuestros ecosistemas y sistemas culturales-edificados se necesitan conservar y mejorar por ser esenciales a la vida presente y futura del pueblo puertorriqueño? O dicho de otra forma, ese armazón o estructura paisajística fundamental es la estructura de apoyo a la vida sin la cual no habría un futuro Puerto Rico. Y, ¿cómo se llega a ella o cómo se define? Pues analizando los elementos del paisaje que son esenciales a la vida en su definición más amplia: los sistemas fluviales principales, las zonas de endemismo mayores, los elementos florísticos y fáunicos críticos, las infraestructuras fundamentales para el funcionamiento de la economía puertorriqueña actual y futura, los lugares históricos que nos dan identidad como pueblo, los enlaces funcionales esenciales entre todos esos elementos, etc., etc.

Esta perspectiva del paisaje, según lo entendemos hoy, es el único marco conceptual que nos abre a la posibilidad de salvar a la sociedad humana y al resto de la naturaleza a la vez porque permite un rol armónico o complementario para lo “natural” y lo edificado en una gama sin fin de posibles interacciones y ontologías – desde la “naturaleza virgen” hasta el Cyborg paisajístico de la infraestructura verde. Lo revolucionario de esta visión es permitir múltiples formas de existir o de ser (ontologías) para la naturaleza, eliminando de una vez y por todas la dicotomía cultural tradicional en Occidente de naturaleza vs. sociedad humana.

El marco conceptual paisajístico de por sí asume que lo humano es natural y lo que se propone es tratar integralmente lo humano con el resto de la naturaleza. Esto no significa abandonar lo humano en favor de lo “natural” sino reconocer que lo humano dentro de lo natural es capaz de aceptar múltiples significados y ontologías, aunque siempre partiendo del mayor bien común o general, incluido el mayor “bien” o “salud” de la “naturaleza”. Implica también aceptar que habrá límites para el crecimiento del impacto o huella humana y que habrá límites también sobre lo que se pueda conservar, pero siempre sobre la base de una funcionalidad ecológica fundamental que hay que preservar y mejorar.

Esta perspectiva del paisaje incluye una visión ecológica de la ciudad donde la naturaleza no sea algo que sobre o esté relegada a rincones estilizados o sea una mera decoración para la arquitectura, sino que sea una integrante fundamental de la vida en la ciudad, apoyando la vida humana pero pudiendo existir también por derecho propio, e inclusive encontrando nuevas formas evolutivas de ser en hibridismo con lo edificado.

Por lo tanto, hay que empezar, no por mirar los planos catastrales, sino por decidir qué del paisaje actual forma ese armazón fundamental para existir y qué visión económica y social nos guiará hacia el futuro. De hecho, tenemos que liberarnos de la esclavitud de planificar pensando sólo en los planos catastrales y a quién afecta tal o cual distrito de calificación. Tampoco podemos pretender conservarlo absolutamente todo. De lo que se trata no es de conservar por conservar sino de proyectar el desarrollo de Puerto Rico basado en una visión de lo que queremos y podemos llegar a ser. Ese proceso podría representarse así:

Obviamente, llegar a esa visión del futuro es difícil, sobre todo en un clima político altamente dividido y cuando tenemos asuntos esenciales, como el estatus político, todavía sin resolver. Pero no podemos rendirnos, o tendríamos que aceptar nuestra “muerte” colectiva.

No hay justificación para que en un país de sólo 9,000 km2, siendo sin duda alguna el país tropical más estudiado del mundo; contando con acceso a la más alta tecnología en percepción remota, sistemas de información geográfica (GIS), etc.; y contando con capital humano más que suficiente, no podamos producir un plan como el que he esbozado. El no incluir esta perspectiva de paisaje nos condenará a seguir planificando de la forma usual y a repetir lo mismo del pasado: planes que son letra muerta ab initio.

Empecemos por lo que la arquitectura paisajista no puede ser hoy. La arquitectura paisajista no puede ser escultura porque la escultura es siempre una imposición sobre el paisaje.

La arquitectura paisajista contemporánea tampoco puede ser la continental europea del siglo XVIII, al modo de André Le Nôtre, porque ésa es al fin y al cabo un avasallamiento del paisaje. Cada vez que tratamos de diseñar el paisaje mediante puras operaciones geométricas estamos calcando a Le Nôtre y negando lo que la arquitectura paisajista puede ser hoy….

Tampoco puede ser el diseño del paisaje al estilo “jardín inglés” del siglo XIX porque ésa es una confección absurda y sentimentalista.

La arquitectura paisajista contemporánea tiene que ser una mediación entre el paisaje “silvestre” y la habitación humana. La manipulación del paisaje (topografía, vegetación, sistemas fluviales, etc.) tiene que ser obvia y evidente, pero revelando a la vez lo mejor del paisaje natural o autóctono del sitio; mediando entre él y el ser humano; permitiendo que el genius loci se exprese y no avasallándolo completamente, no haciéndolo esclavo sino “socio” de la habitación humana. Las operaciones que se realicen en el paisaje deben ir dirigidas a alcanzar el doble objetivo de:

1. Revelar y fortalecer los sistemas y procesos naturales y culturales locales (que le dan carácter particular al paisaje local); y

2. Permitir el uso y disfrute del paisaje por los seres humanos, canalizando sus expresiones culturales en ese tiempo-espacio específico con el arte como lenguaje.

El lograr estos dos objetivos simultáneamente y de forma excelsa y única es el arte fundamental de la arquitectura paisajista. El entender los sistemas naturales y culturales que forman el entretejido del paisaje (sus patrones y procesos) y saberlos manipular es la ciencia fundamental de la arquitectura paisajista.

You must be logged in to post a comment.